A stress fracture is a small crack in a bone or severe bruising within a bone. Most stress fractures are caused by overuse and repetitive activity. They are common in runners and athletes who participate in running sports.

Stress fractures usually occur when people change their activities. For example, trying a new exercise, rapidly increasing the intensity of their workouts, or changing the workout surface (jogging on a treadmill vs jogging outdoors) can potentially be problematic. Also, if osteoporosis or other disease has weakened the bones, just doing everyday activities may result in a stress fracture.

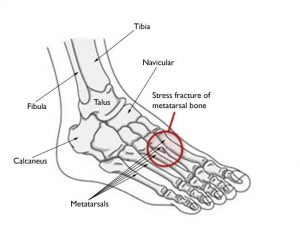

The weight-bearing bones of the foot and lower leg are especially vulnerable to stress fractures because of the repetitive forces they must absorb during activities like walking, running, and jumping.

Refraining from high impact activities for an adequate time is key to recovering from a stress fracture in the foot or ankle. Returning to activity too quickly can delay the healing process and increase the risk of a complete fracture. Should a complete fracture occur, it will take far longer to recover and return to activities.

Where do stress fractures occur?

Stress fractures most often occur in the second and third metatarsals, which are thinner (and usually longer) than the neighbouring first metatarsal. This receives the most significant impact on your foot as you push off when you walk or run. Stress fractures also occur in the leg bones, the heel and bones of the mid-foot where major tendons insert.

Repetitive forces result in microscopic damage to the weight-bearing bones, and they do not have enough time to heal between exercise sessions.

Bone is in a constant state of turnover—a process called remodelling. New bone develops and replaces older bone. Suppose an athlete’s activity is too great. In that case, the breakdown of older bone occurs rapidly — it outpaces the body’s ability to repair and replace it. As a result, the bone weakens and becomes vulnerable to stress fractures.

You can get a stress fracture if you increase the frequency of activity—such as exercising more days per week. It can also be in the duration or intensity of activity—such as running longer distances.

Even for the non-athlete, a sudden increase in activity can cause a stress fracture. For example, if you infrequently walk on a day-to-day basis but end up walking excessively (or on uneven surfaces) while on vacation, you might experience a stress fracture. A new style of shoes can lessen your foot’s ability to absorb repetitive forces and result in a stress fracture.

Increased risks for stress factors

Bone Insufficiency

Conditions that decrease bone strength and density, such as osteoporosis and certain long-term medications, can make you more likely to experience a stress fracture. This can occur even when performing everyday activities. For example, stress fractures are more common in the winter months, when Vitamin D is lower in the body.

Studies show that female athletes are more prone to stress fractures than male athletes. This may be due, in part, to decreased bone density from a condition that doctors call the “female athlete triad.” When a girl or young woman goes to extremes in dieting or exercise, three interrelated illnesses may develop eating disorders, menstrual dysfunction and premature osteoporosis. As a female athlete’s bone mass decreases, her chances of getting a stress fracture increase.

Poor Conditioning

Doing too much too soon is a common cause of stress fracture. This is often the case with individuals who are just beginning an exercise program. It also occurs in experienced athletes, though. For example, runners who train less over the winter months may be anxious to pick up right where they left off at the end of the previous season. Instead of starting slowly, they resume running at their previous mileage. This situation in which athletes increase activity levels and push through any discomfort, and do not allow their bodies to recover can lead to stress fractures.

Improper technique

Anything that alters the mechanics of how your foot absorbs impact as it strikes the ground may increase your risk for a stress fracture. For example, suppose you have a blister, bunion, or tendonitis. In that case, it can affect how you put weight on your foot when you walk or run and may require an area of bone to handle more weight and pressure than usual.

Change in surface

A change in training or playing surfaces, such as a tennis player going from a grass court to a hard court, or a runner moving from a treadmill to an outdoor track, can increase stress fracture risk.

Improper equipment

Wearing worn or flimsy shoes that have lost their shock-absorbing ability may contribute to stress fractures.

Stress fracture symptoms

The most common symptom of a stress fracture in the foot or ankle is pain. The pain usually develops gradually and worsens during weight-bearing activity. Other symptoms may include:

- Pain that diminishes during rest

- Pain that occurs and intensifies during normal, daily activities

- Swelling on the top of the foot or the outside of the ankle

- Tenderness to touch at the site of the fracture

- Possible bruising

First aid

See your doctor as soon as possible if you think you have a stress fracture in your foot or ankle. Ignoring the pain can have serious consequences. The bone may break completely.

Until your appointment with the doctor, follow the RICE protocol. RICE stands for rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

- Rest. Avoid activities that put weight on your foot. If you have to bear weight for any reason, make sure you are wearing a very supportive shoe. A thick-soled cork sandal is better than a thin slipper.

- Ice. Apply ice immediately after the injury to keep the swelling down. Use cold packs for 20 minutes at a time, several times a day. Do not apply ice directly on your skin.

- Compression. To prevent additional swelling, lightly wrap the area in a soft bandage.

- Elevation. As often as possible, rest with your foot raised higher than your heart.

- NSAIDS: In addition, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, can help relieve pain and reduce swelling.

Doing too much too soon is a common cause of stress fracture. This is often the case with individuals who are just beginning an exercise program-but it occurs in experienced athletes, as well. For example, runners who train less over the winter months may be anxious to pick up right where they left off at the end of the previous season. Instead of starting off slowly, they resume running at their previous mileage. This situation in which athletes not only increase activity levels, but push through any discomfort and do not give their bodies the opportunity to recover, can lead to stress fractures.

Medical examination

Your doctor will discuss your medical history and general health. They will ask about your work, activities, diet, and any medications you are taking. Your doctor must be aware of your risk factors for stress fracture. Suppose you have had a stress fracture before. In that case, your doctor may order a full medical work-up with laboratory tests to check for nutritional deficiencies such as low calcium or Vitamin D.

After discussing your symptoms and health history, your doctor will examine your foot and ankle. During the examination, they will look for areas of tenderness and apply gentle pressure directly to the injured bone. Often, the key to diagnosing a stress fracture is the patient’s reaction to pain in response to this pressure. Pain from a stress fracture is typically limited to the area directly over the injured bone. It is not generalized over the whole foot.

Imaging Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

X-rays: X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Since a stress fracture starts as a tiny crack, it is often difficult to see on a first x-ray. The fracture may not be visible until several weeks later, when it has started to heal. After a few weeks, a type of healing bone called callus may appear around the fracture site. In many cases, this is the point at which the fracture line becomes visible in the bone.

Stress fracture treatment

The goal of treatment is to relieve pain and allow the fracture to heal so that you are able to return to your activities. Following your doctor’s treatment plan will help you return to activities faster and prevent further damage to the bone.

Treatment will vary depending on the location of the stress fracture and its severity. The majority of stress fractures are treated nonsurgically.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In addition to the RICE protocol and anti-inflammatory medication, your doctor may recommend that you use crutches to keep weight off your foot until the pain subsides. Other recommendations for nonsurgical treatment may include:

- Modified activities. It typically takes from 6 to 8 weeks for a stress fracture to heal. During that time, switch to activities that place less stress on your foot and leg. Swimming and cycling are good alternative activities. However, you should not resume any physical activity that involves your injured foot or ankle – even if it is low impact – without your doctor’s recommendation.

- Protective footwear. To reduce stress on your foot and leg, your doctor may recommend wearing protective footwear. This may be a stiff-soled shoe, a wooden-soled sandal, or a removable short-leg fracture brace shoe.

- Casting. Stress fractures in the fifth metatarsal bone (on the outer side of the foot) or the navicular or talus bones take longer to heal. Your doctor may apply a cast to your foot to keep your bones in a fixed position

Surgical Treatment

Some stress fractures require surgery to heal properly. In most cases, this involves supporting the bones by inserting a type of fastener. This is called internal fixation. Pins, screws, and/or plates are most often used to hold the small bones of the foot and ankle together during the healing process.

Recovery

In most cases, it takes from 6 to 8 weeks for a stress fracture to heal. More serious stress fractures can take longer. It can be hard to be sidelined with an injury, but returning to activity too soon can put you at risk for larger, harder-to-heal stress fractures and an even more extended downtime. Reinjury could lead to chronic problems, and the stress fracture might never heal properly.

Once your pain has subsided, your doctor may confirm that the stress fracture has healed by taking x-rays. A computed tomography (CT) scan can also help determine healing, especially in bones where the fracture line was initially hard to see.

Once the stress fracture has healed and you are pain-free, your doctor will allow a gradual return to activity. During the early rehabilitation phase, your doctor may recommend alternating days of activity with days of rest. This gives your bone the time to grow and withstand the new demands being placed upon it. As your fitness level improves, slowly increase the frequency, duration, and intensity of your exercise.

This x-ray of the mid-foot shows screws placed in the navicular bone to keep the fracture in a fixed position during healing.

Reproduced with permission from Shindle MK, Endo Y, Warren RF, Lane JM, Helfet DL, Schwartz EN, Ellis SJ: Stress fractures about the tibia, foot, and ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg March 2012 vol. 20 no. 3 167-176.

Prevention

The following guidelines can help you prevent stress fractures in the future:

- Eat a healthy diet. A balanced diet rich in calcium and Vitamin D will help build bone strength.

- Use proper equipment. Old or worn running shoes may lose their ability to absorb shock and can lead to injury. In general, athletic shoes should have a softer insole, and a stiffer outer sole.

- Start new activity slowly. Gradually increase your time, speed, and distance. In most cases, a 10 percent increase per week is appropriate.

- Cross train. Vary your activities to help avoid overstressing one area of your body. For example, alternate a high-impact sport like running with lower-impact sports like swimming or cycling.

- Add strength training to your workout. One of the best ways to prevent early muscle fatigue and the loss of bone density that comes with aging is to incorporate strength training. Strength-training exercises use resistance methods like free weights, resistance bands, or your own body weight to build muscles and strength.

- Stop your activity if pain or swelling returns. Rest for a few days. If the pain continues, see your doctor.